- Cambridge Arts>

- News>

- Visionary Paintings By Danehy Park Artist With Autism Coming To Cambridge Arts Gallery

Visionary Paintings By Danehy Park Artist With Autism Coming To Cambridge Arts Gallery

4/10/2023 • 15 months ago

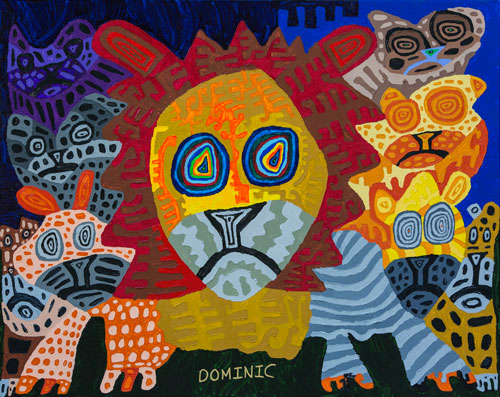

Dominic Killiany’s visionary paintings of Boston’s Zakim Bridge, street signs, fish, a lion, zebra, elephant and giraffes were reproduced as murals in the Louis A. DePasquale Universal Design Playground at Danehy Park.

Now see his original works in the exhibition “What I See” on view at Cambridge Arts’ Gallery 344, 344 Broadway, second floor, Cambridge, from May 1 to Aug. 31, 2023. Join us for a public reception on May 1 from 5 to 7 p.m. Gallery events are free and open to all.

Killiany, a prolific artist living with autism, has resided in a group home in Watertown since summer 2020 and has lately been painting at Turtle Studios in Newton. The exhibition will also feature the intricate pencil drawings that lie hidden beneath the bright, thick acrylic paint.

The Universal Design Playground, completed in 2022, is the first developed by the City of Cambridge to fully incorporate Universal Design—a concept that all the playground features should be as welcoming to and as usable as possible by people of all abilities. The 30,000 square foot play area is located between Field Street and the Briston Arms residential complex.

"We are so honored as a family that Dominic's artwork was chosen for perpetuity to represent this Universal Design Playground,” his mother, Susan Cicconi, said. "Children as well as adults can skip and jump to happy, colorful, patterns and feel the collective tribe of animals as our own families. The paintings spark conversation and imagination. Some of them take us to familiar places and others are like giant puzzles and mazes. It's a really fun place."

Susan Cicconi says, "As a family navigating autism, we and Dominic were particularly honored to have his art featured in the Universal Design Playground in a way that could connect with and support other families with special needs."

Killiany has been drawing since he was little. “He’s mostly nonverbal, however he has language, he is articulate, he understands everything. The problem is expressing,” Cicconi says. “…The thing that caught our attention at age 3 was his ability to reproduce street signs in chalk on our driveway. To perfection.”

At age 14, “he took an interest in painting-by-numbers,” Cicconi says. “If you think of paint-by-numbers, the diagrams look like little puzzle pieces. … He focused mainly on how to make shapes to form a composition.” The following year, “he was making his own compositions.”

“I think he puts everything together like a puzzle or paint-by-numbers” his father, Michael Killiany, says.

Killiany painted landscapes, then animals. He reinterprets photos as line drawings in pencil, then fills each shape in with paint. At times, he numbered his own sketches like paint-by-number diagrams before painting them. Then he numbered all the spaces in sequence. “There was a period of a year, maybe two, where he had to number all the spaces,” Cicconi says. “It’s this sequencing thing he does. The numbers act as symbols, maybe they have meaning to him.” He’s partial to twos and twenty-twos and thirty-threes.

“He wants 10 tubes of paint for one canvas,” Cicconi says. If allowed, he prefers to squeeze out entire tubes to use in a single painting, painting it on thick, mixing colors until he gets his favorite yellows and whites and oranges—“cantaloupe orange, sweet potato orange, mandarin orange, or apricot orange.”

These days, Killiany’s favorite subjects are wild animals (lions, tigers, leopards, koalas, lionfish), cityscapes (Zaikim Bridge, Longfellow Bridge and Hancock Tower, Statue of Liberty), clocks, numbers, geometry, and shapes interlocked like puzzles. Killiany would only paint lions or tigers, Cicconi says, if she didn’t nudge him to try, say, the Zaikim Bridge—a landmark on the way home from his weekly drives with his father. Killiany and his mother search the internet for images until one catches his eye.

“The inspiration is key,” Michael Killiany says.

“I’ve tried to ask him why he likes those animals. He can’t respond to that question,” Cicconi says. “I just think that in another life he was a lion or tiger.”

“Covid hit him really hard and he stopped painting for 2021. He’s back now, he’s painting,” Cicconi says. “We found a fantastic studio space for him to paint.” He’ll often paint for eight hours at a stretch. “Art is therapy for Dominic. It’s when he’s most focused, most happy.”

Killiany was a 2021 finalist in the VSA (Very Special Arts) Emerging Young Artists Program, which includes his painting being exhibited at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., and in a traveling exhibition. Cicconi says sales of Killiany’s artworks help pay to keep some 150 paintings in storage—and hopefully will increase to become an income for him.

“Every kid with autism has a strength,” Cicconi says, “you just have to find it.”